Criminal Justice Fairness: Government Funded Counsel, Rowbotham Applications and Legal Aid

Update – May 2015: For more information on legal funding and Rowbotham applications check out Chelsea Moore’s blog post at Abergel Goldstein & Partners.

Over the last number of years there has been a dramatic increase in the number of applications brought by individuals accused of serious criminal offences seeking court orders for government funded legal counsel.

The vast majority of these applications (called Rowbotham applications) are successful – the government is ordered to pay the legal bill.

This week I appeared on CBC’s Ottawa Morning to discuss the impact of these applications, why they are necessary, why their numbers are increasing and why the public should care.

The audio of my conversation with Robyn Bresnahan discussing this important issues can be found below.

The starting point in any discussion about legal funding is an accused person’s Constitutional right to a fair trial.

Fairness is the foundation of our criminal justice system. It is only through the operation of fairness that society can have full confidence in the justice system. It is only when fairness is ensured that we can rest well knowing a conviction was just and proper.

One needs to look no further than the litany of recently uncovered wrongful convictions to see the results of an unfair system. Each wrongful conviction erodes confidence in the justice system and results in devastating personal cost to the wrongfully convicted individual.

The devastating impact of wrongful convictions is recognized in the golden thread of our justice system – the presumption of innocence. As William Blackstone said: It is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer.

Our legal system is, however, also adversarial. The state is a well funded legal machine comprised of skilled prosecutors, expert witnesses, and police investigators. An unrepresented accused, lacking legal training, is in no position to defend themselves against such an adversary.

Defence counsel play an integral role in ensuring criminal justice fairness. Defence counsel act as a bulwark against the power of the state and are essential in ensuring fairness when an accused is charged with an offence that is complex and can result in serious liability.

It is in this context that when an accused has been denied legal aid and cannot afford counsel that the courts have the power to order the government fund the accused’s defence (It should be noted that in these circumstances defence counsel are paid at the legal aid rates – well below market value and significantly less than their Crown Attorney adversaries)

The Ontario Court of Appeal held in the seminal case of R. v. Rowbotham:

To sum up: where the trial judge finds that representation of an accused by counsel is essential to a fair trial, the accused, as previously indicated, has a constitutional right to be provided with counsel at the expense of the state if he or she lacks the means to employ one. Where the trial judge is satisfied that an accused lacks the means to employ counsel, and that counsel is necessary to ensure a fair trial for the accused, a stay of the proceedings until funded counsel is provided is an appropriate remedy under s. 24(1) of the Charter where the prosecution insists on proceeding with the trial in breach of the accused’s Charter right to a fair trial.

Over the last few years the number of Rowbotham applications has dramatically increased – my office has seen a ten fold increase in these applications. This increase is in part due to the escalating complexity of criminal cases (cause in no small part by new Conservative criminal justice legislation).

However, the primary cause for the increase in funding applications can be linked to issues with the Legal Aid program itself.

In short more accused are being denied legal aid – even for serious charges – even when they have no resources to hire counsel. It is at this point that the funding and operation of Legal Aid runs into conflict with principles of fairness.

This should be an issue of concern – after all it is the principle of fairness that gives society the confidence in our legal system – confidence that gives the system necessary credibility.

The Ontario Legal Aid plan was born in the 1960s and was driven by the progressive belief that a person is entitled to legal representation as a matter of right. The legal aid plan recognized that in our adversarial system any person who is too poor to hire a lawyer cannot be assured a fair trial.

As said by John Honsberger in his 1968 paper on the Ontario Legal Aid Plan:

It is not so much that the law should be the same for the rich and the poor but that the burden should be equal. Otherwise the equality may be the sort that Anatole France had in mind when he said: “The law in all its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges on rainy nights, to beg on the streets and to steal bread.”

In 1968 the Ontario’s legal aid budget was 6.7 million dollars. Current funding of legal aid has not matched the rate of inflation. The Ontario legal aid plan – once called one of the most progressive programs in the world – is underfunded and increasingly unable to fulfill its mandate.

This underfunding – which is particularly acute in the criminal justice sector – has led to an increase in the number of individuals denied legal aid.

These denials often seem (and sometimes are) unprincipled. For example, Legal Aid often denies an accused the ability to change lawyers (effectively denying legal counsel) – even when the accused’s lawyer is unable to represent them for ethical reasons (see: R. v. Hafiz at para 19-21).

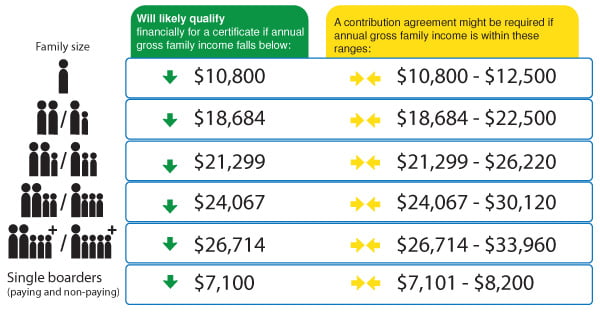

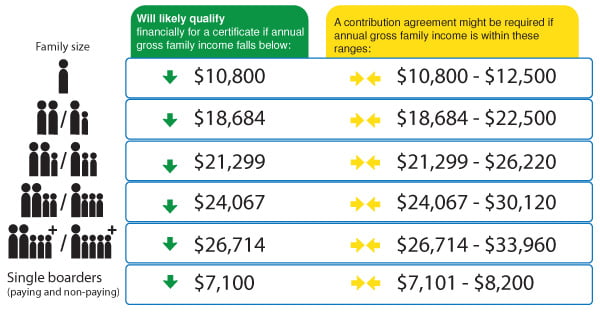

The majority of denials however are driven by Legal Aid’s regressive financial means test. To qualify for Legal Aid – even for the most serious charges – an accused must live below the poverty line.

I have had clients denied Legal Aid for making as little as a few hundred dollars more than the financial cut off.

The robotic application of these antiquated financial eligibility tests results in unfairness, increased expenses and is inconsistent with a 2008 review of Legal Aid (ordered by the Ontario Government) which found:

Financial eligibility criteria need to be significantly raised to a more realistic level that bears some relationship to the actual circumstances of those in need. They should be simplified and made more flexible so that services could be provided along a sliding scale of eligibility with broadened rules for client contributions. The criteria also need to be brought into line with anti-poverty measures used elsewhere in the social welfare system and adjusted on a regular basis.

The increase in the number of Rowbotham applications results in wasted tax payer money, wasted court time, and necessary delays.

Most Rowbotham applications are granted and include provisions that defence counsel are to be paid for the time it took to bring the application (typically 20-50 hours of work). This cost (plus the coast of the court time) can add thousands of dollars to the final bill.

In most cases it would have been less expensive (and more efficient) for fair and appropriate funding decisions to be made at first instance – as opposed to after protracted litigation.

Litigated Rowbotham application represent the tip of the iceberg with respect to waste. For every application that makes its way to court countless applications are resolved on the eve of trial. In other words – the government agrees that the application would have been granted and agrees to fund an accused’s defence. In these situations counsel is still paid for their preparation time, court time is still wasted, and gag orders are routinely incorporated into the funding agreements to limit disclosure of what happened.

The public should be concerned that government money is being wasted and that the costs of ideological federal criminal justice policy are being passed to the poor.

More importantly the public should be troubled that Legal Aid funding decisions are being made that result in potential unconstitutional unfairness.

A well funded and appropriately operated Legal Aid system is the (small) price that must be paid for an effective and fair justice system – this was true in the 1960’s and it remains true today.